LINCOLN HIGHWAY NEWS IS A BLOG BY BRIAN BUTKO

The Boy Scout Safety Tour visited the Linn County Courthouse, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on July 19, 1928. From left, Carl Zapffe, Edward Pratt, Mark Hughes, driver Reese Davis, Bernard Queneau, BSA Tour Manager Charles Mills, BSA Director of Demonstrations Reno Lombardi, and their Reo Speed Wagon.

If you attended a Lincoln Highway event in the past decade, you know there was only one celebrity who fans waited to see: Bernie Queneau, with his deep voice and big smile. Of course, his world was much larger than the Lincoln Highway. When I last spoke with him, an interview actually, he asked if we could talk about something else. “There was more to my life than that trip” he said, not grouchy but proudly.

Still, to Lincoln Highway fans he will always be the Scout on the 1928 coast-to-coast Safety Tour, the last connection to a long-gone era when Model T’s dominated the dusty/muddy, roads.

Bernie was born in Liege, Belgium, on July 14, 1912—Bastille Day he liked to point out—two months before Carl Fisher gathered auto industry friends to propose his crazy cross-country highway idea. Bernie had vague memories of WWI, and then at 13, his family moved to Minneapolis. Thanks to his advanced education, they made him a high school sophomore. His family moved again to New Rochelle, New Jersey, where he graduated in 1928 at age 15.

He entered a contest for Eagle Scouts to go to Africa and was one of seven finalists. After three were chosen, Bernie and the remaining three were offered a tour along the Lincoln Highway that would promote both Scouting and the road itself, which was being superseded (as were all named trails) by the Federal highway numbering system. Much of the Lincoln Highway from Pennsylvania to Wyoming was marked as U.S. 30, but they were different paths, and many bypassed parts of the Lincoln never did receive a number. Those are the parts the Scouts would have traveled.

I first met Bernie when LHA President Esther Oyster tracked him down in 1997. I was a founding director of the LHA and had published my first book about the road the year before. Esther was looking for a special speaker at the upcoming LHA conference in Ohio and was surprised to find one of the Scouts still living. Bernie was 84 and here in my hometown of Pittsburgh. She arranged for us to interview him on March 20 at my workplace, the Senator John Heinz History Center, where I still work. Bernie was amazed that anyone had heard of his road trip seven decades earlier, let alone might be interested in it.

Esther and Bernie at the fun, informal premier of Rick Sebak’s PBS program about the Lincoln Highway. Sebak’s impromptu showing of clips on the wall pleased fans crowded into the Road Toad near Ligonier, Pa., September 20, 2008.

Esther and Bernie met again at the 2002 LHA conference in San Francisco, where he dedicated a replacement marker at the Western Terminus, and a few months later they invited me to lunch. Plans were made for the William Penn Hotel, a prestigious venue in downtown Pittsburgh, opened 1916. We three reunited at the History Center, and as we walked outside I asked Bernie where he was parked. “We’ll walk” he said and for the next seven blocks it was hard to keep up with this sprightly 90-year-old! Their treat that day was to tell me they’d gotten engaged!

Bernie liked to joke about meeting Esther’s family, that they teased him whether he had any piercings or if he worried about being 12 years older. He joked back that he thought Esther would be sufficiently mature. They were married and in Summer 2003 they re-drove his trip across the country with an LHA tour group that celebrated the 90th anniversary of the Lincoln Highway, the 75th anniversary of the Scout trip, and their marriage.

Every few years our paths would cross, usually at a Lincoln Highway event. Last year, after a historical society evening banquet, the older audience was ready to go home, but Bernie ordered another bottle of wine. After lunch just a few months ago, he jumped behind the wheel of his new car and drove Esther home on the Penn-Lincoln Parkway, Pittsburgh’s frantic 4-lane successor to the old Lincoln Highway through town.

The History Center will open a WWII exhibit next Spring, hence my invitation to Bernie for another oral history. The three of us met up here once again, and for a couple hours he held us spellbound with first-hand recollections of being in the Navy 1939-1946. He used his Ph.D. in Metallurgy to investigate many important applications, from oxygen tanks to aircraft armor to improved ballistics. After the war, he joined U. S. Steel, rising in 1970 to General Manager Quality Assurance for the entire company, which was producing 25 million tons of steel a year. He retired in 1977 only to become a Consulting Engineer, not really retiring for another decade.

Of course, even real retirement for Bernie was busier than a workday for the rest of us. He volunteered for Meals on Wheels, as a hospital escort, and more recently at the used book store at his nearby Mt. Lebanon Library. He and Esther saw a great deal of the world together. He was even a bit late to his own big 100th birthday party, having toured the city all day.

On Saturday, December 6, 2014, he was bestowed the rare Distinguished Eagle Scout Award for outstanding career achievement, on Esther’s 90th birthday. He passed away hours later, on Sunday, Pearl Harbor Day.

There is so much more to his life but it’s the Scout trip that always fascinated Lincoln Highway fans. His 1928 diary holds the precious insights of a teenager on an arduous and monotonous trip.

In New Jersey: “We saw the mayor and veteran of Civil War…. we did over 60 on the crowded highway.”

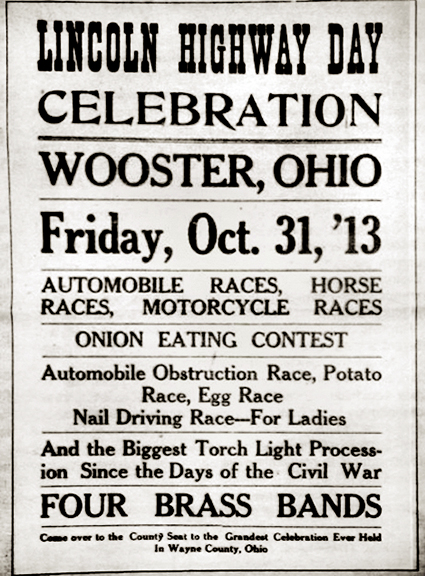

“Ohio is full of pigs, cattle, bad roads, and rain.”

And Utah: “On and on and on over the worst U.S. route I ever hope to see.”

We’ll miss his honesty, his thoughtful observations, his sense of humor, his love of history and good food. Most of all, I will miss his steady demeanor behind all those other things. As Esther likes to say, he was an old-school gentleman. When in his company, you felt you should do better too, be a better person … and be at least half as active. We’ll miss Bernie but he surely has 102 years of friends waiting for him….

Tired Scouts in a Hudson convertible on the long trip home. Bernie is at right.