LINCOLN HIGHWAY NEWS IS A BLOG BY BRIAN BUTKO

The Lincoln Highway was officially dedicated on October 31, 1913, with bonfires, parades, concerts, and speeches along the coast-to-coast route. Lots of news articles can be found that describe the festivities — from masquerade balls to farmers placing jack-o-lanterns on fence posts — but was there a reason behind celebrating this momentous occasion on, of all days, Halloween?

It’s logical that the LHA would have documented its reasons but Kathleen Dow (Archivist and Curator of the Transportation History Collection at the University of Michigan Special Collections Library) says neither the minutes from the LHA’s formation on July 1 nor those from October 27 mention the dedication on October 31.

The 31st would have been the 49th anniversary of Nevada’s statehood, and though that was important to President Lincoln’s re-election in 1864, it was not a close enough connection to the new road.

The Washington Herald (October 6, 1913) noted that LHA directors had just met in Detroit, coinciding with the Third American Good Roads Congress, and “discussed the arrangements for the dedication celebrations on the night of October 31 at every point along the proposed highway, and the discourses to be delivered by the clergy on Sunday [Nov. 2].” Still, no reason was given.

However, we can guess with great certainty that the celebratory nature of Halloween itself, especially being on a Friday that year, was the reason for choosing October 31.

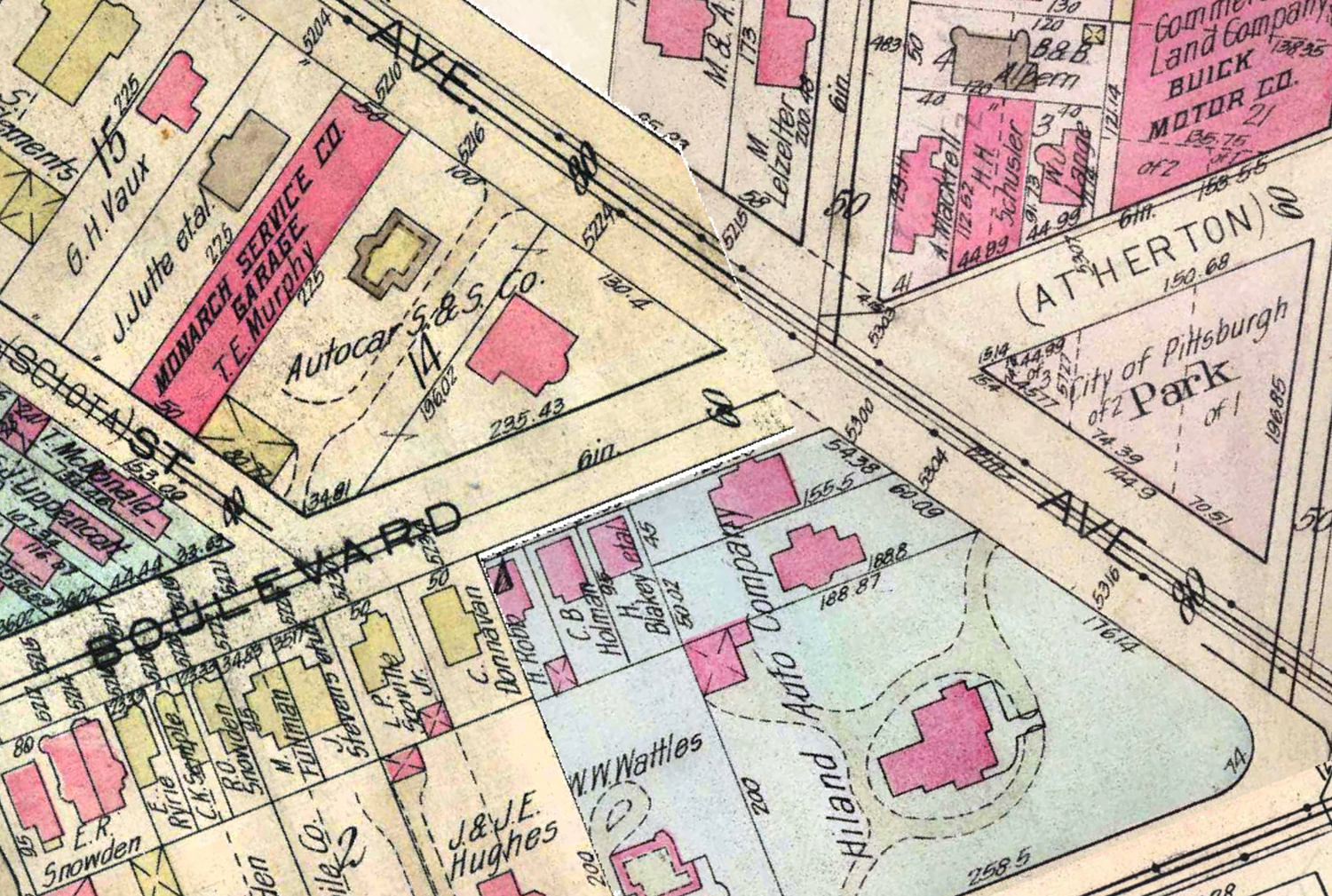

Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 26, 1913.

The U.S. was just beginning to celebrate “Hallowe’en” in 1913. Trick-or-treating did not become mainstream until the 1950s but there was a centuries-old tradition of fires, parades, and dressing up on All Hallows’ Eve that recent immigrants had brought to America. LHA leaders were masters at harnessing public relations, and what better date to choose for fanciful nighttime celebrations than the one day a year that such activities already took place?

The San Francisco Chronicle (October 26) hinted at just that: “It is the idea of the boosters of the transcontinental motorway that the dedication be a sort of spontaneous expression of gratification and it has been left to each city and town along the route of the proposed highway to devise and carry out its own plan of celebration.”

On the 31st, the Chronicle added, “The exercises will be a fitting Halloween celebration, but overshadowing all the goblins and ghosts of the evening there will be the spirit of the great national boulevard that is to be constructed during the next three years.”

In the dedication proclamation from Wyoming, Governor Joseph Carey stated “It is thought especially fitting that on the evening of October 31st there should be an old-time jollification to include bonfires and general rejoicing; this for the purpose of impressing upon the people and especially the younger generation-the services and unselfish life of Lincoln, and for the further purpose of painting a big picture so far as amusements are concerned of the highway which is to cross our state.”

Some of that wording likely came from an LHA press release, as an article in the November 1 Salt Lake Tribune similarly noted it had been “the request of the directors of the Lincoln Highway to make October 31 an evening of general rejoicing.” In the next day’s Deseret Evening News, the dedication recap included that the LHA had adopted the now-familiar oval emblem with U.S. map in the middle, and that drawings of it were being sent to contributors.

Nebraska’s governor also declared October 31 a holiday, and Omaha had perhaps the largest event in the country. Celebrations started across the Missouri River in Council Bluffs, Iowa, at 12:01 a.m. with fire bells, factory whistles, and a torchlight parade. The Union Pacific Railroad donated carloads of railroad ties and an oil company helped fuel a massive bonfire later that night attended by 10,000 people, plus supplied smaller bonfires lining the route for 300 miles to North Platte.

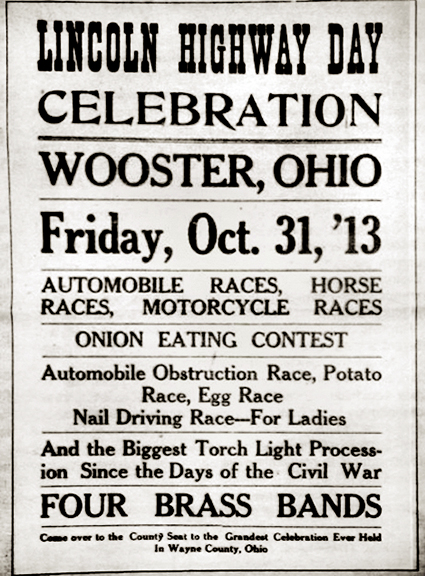

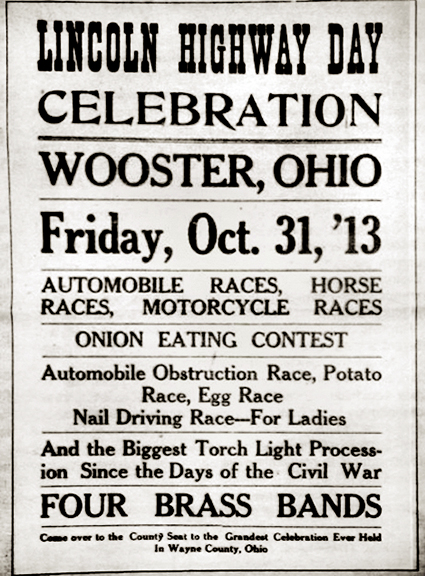

“Lincoln Highway Day” in Wooster, Ohio, included everything from motorcycle races to an onion eating contest. ~Courtesy Francis Woodruff, Dalton Gazette, via Mike Hocker.

As for Nevada, Governor Tasker Oddie’s proclamation made the statehood connection only a pleasant coincidence: “Friday the 31st day of October, by statute a legal holiday, is the 49th anniversary of the admission of Nevada into the Union — the only state admitted during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. It happens that on the evening of this day, in all the cities and towns of all the states through which the proposed Lincoln Highway will pass, public services will be held, celebrating the naming of the route.”

Motor Age magazine (November 6) reported afterwards on some of the national merriment, most of which included parades and especially bonfires. Some towns, like Wooster, Ohio, renamed the road through the county as “Lincoln Highway” and a restaurant in town rechristened itself the Lincoln Highway Cafeteria. In fact, shops there began the 31st with “Lincoln Highway Day bargains” before closing at noon to start the revelry.

In Wyoming, the dedication did nothing to stem a long-running controversy about the routing between Laramie and Rawlins. The route was popularly believed to follow the more direct route via Elk Mountain, but directors favored arcing north through Medicine Bow, 18 miles longer but with calmer winds and fewer gates. The Elk Mountain Republican (November 6) reported on that town’s speeches, dancing, and bonfire but Motor Age noted that citizens there and in Medicine Bow “cast defiance at the other, both issuing statements to show that they had been placed on the official route.” The LHA’s 1916 road guide was still trying to mend fences by mentioning that “an alternate route to Rawlins is offered via Elk Mountain.”

Decades later, the Lincoln had been superseded by federal highways and the Interstates, yet the road’s name and mystique endured. On the 49th anniversary in 1962, the Chicago Daily Tribune noted that farmers still celebrated the highway’s anniversary on Halloween—and that “Jack-O-Lanterns still mark the way.”

Brian Butko is author of Greetings from the Lincoln Highway, revised edition coming in 2019, and the LHA’s official centennial publication The Lincoln Highway: Photos Through Time.